Dec 14 2023

Published by

NYU Shanghai

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic swept the world, roughly 300 million people globally were suffering from depression. As the pandemic forced billions of people into periods of isolation and raised stress levels over everything from personal relationships to job and food security, depression and anxiety went up by more than 25% in just the first year of the pandemic alone according to WHO, raising global mental health concerns.

A recent study led by NYU Shanghai’s Center for Global Health Equity (CGHE) reveals that strong social network support, such as having close friends, and practical assistance, like financial support or childcare, can act as a protective shield against symptoms of depression by reducing the feeling of loneliness, especially for men.

The study, published in BMJ Mental Health, examined the stress-buffering process of social support on depressive symptoms using data from the Covid Mental Health Survey, an international study led by Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, the Netherlands and conducted on over 4,000 adults from 13 countries during the early worldwide outbreak of COVID-19, a period perceived as stressful by most.

“Most of the existing work on social support and mental health are cross-sectional studies, from which we were only able to see connections between social support and depression without establishing a clear association between them,” said Professor of Global Public Health Brian Hall, director of the Center for Global Health Equity at NYU Shanghai, who led the research team. “Our study addresses this issue by applying the ‘longitudinal network methodology,’ enabling us to explore the association between social support and depression symptoms and establish direct links between them.”

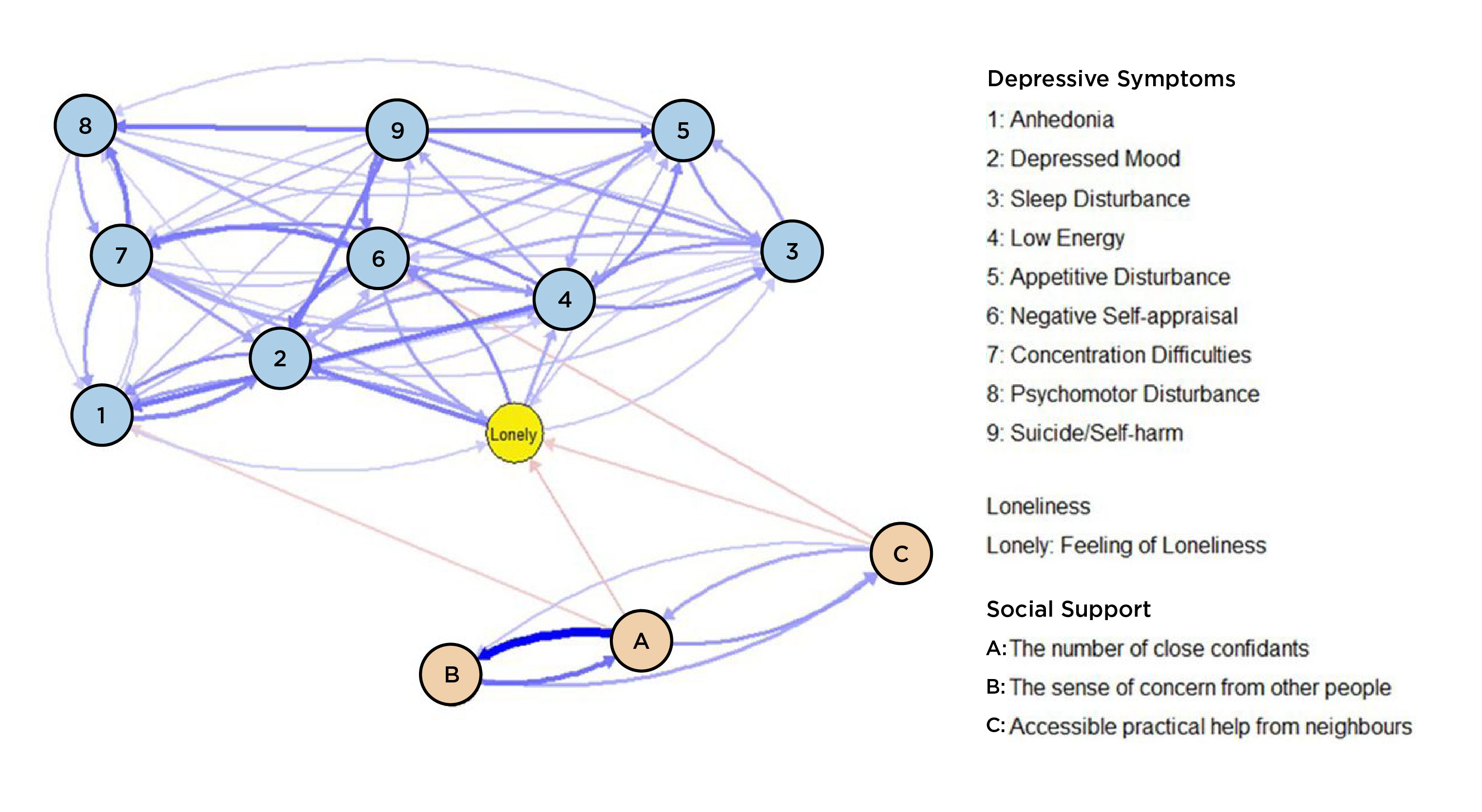

The study delves into the dynamic relationships between nine depressive symptoms and the stress-buffering process of social support on these symptoms. Findings show that loneliness can play a key mediating role.

The study delves into the dynamic relationships between nine depressive symptoms and the stress-buffering process of social support on these symptoms. Findings show that loneliness can play a key mediating role.

“Instead of treating depression as a whole disease, our study breaks it into nine different symptoms, including anhedonia, depressed mood, and suicide/self-harm, and treats each symptom individually so that we can delve into the dynamic relationships between them,” explained the paper’s second author NYU Shanghai Class of 2024 undergraduate Li Yifan, who conducted the data analysis. “We then incorporate social aspects to think about the broader social determinants of each depressive symptom, enhancing our understanding in a more comprehensive way.”

Through analysis, the study finds that having a higher number of close friends and accessible practical support from one’s social network were directly associated with decreased anhedonia and negative self-appraisal symptoms. Support from others also indirectly affects depression symptoms through the mediation of loneliness. Social support was negatively associated with loneliness, which, in turn, was associated with decreased depressed mood and negative self-appraisal.

“Our results showed that emotional support doesn’t really help mitigate depression symptoms. This might contradict common sense, as we would usually think that if we see someone in a low mood, it’s always helpful to give them some emotional support,” said first author Li Gen, formerly a postdoc fellow at CGHE. “It would be more helpful if people have a larger social network or if people can get some instrumental support such as food or even cash.”

With the recent announcement by the WHO of a new Commission on Social Connection to address the global public health threat of loneliness, there is more attention being paid to addressing loneliness through promoting social connection. “Our findings bring further evidence to support this assertion and we’d like to urge the consideration of loneliness in future mental health interventions,” said Hall.

Another highlight of the study is that it finds that men especially can benefit more from social support. “Our findings show that self-esteem is really consequential for men because of the general social roles that men play. During the pandemic, many people lost jobs, their ability to generate income for households, and to maintain their socially sanctioned roles,” said Hall. “I think from a global data set, we’re seeing that men’s self-esteem is incredibly important for their mental health.”

Following this study, Hall’s team is looking into different intervention pathways, including community-based mental health interventions that bolster community connectedness. “Having people within a social network that you could rely on for instrumental support sounds a lot like the Chinese concept of ‘guanxi’ [or social network], which cascades across Chinese culture,” said Hall. “Now research proves that it’s incredibly consequential for mental health as well,” he added.“From a community-based perspective, we want to improve people's social connectedness to create a mental health buffering effect at the community level which can improve community resilience, and aid disaster or public health preparedness efforts.”

Meanwhile, Hall continues to foster collaboration across academic training levels and disciplines at CGHE. “CGHE always encourages students of all training stages to work directly on research projects. Take this study as an example - Yifan, as an undergraduate, had the opportunity to apply the sometimes highly theoretical or very technical knowledge acquired from classes to solving real-world public health problems; Gen, as a postdoc, continued to consolidate his expertise in the field and gained experience leading an internationally collaborated project, preparing him better for his future career path,” Hall said.

“We’re leveraging the strengths at NYU Shanghai across disciplines and training backgrounds to bring to bear in our public health research agenda, actually solving challenges or providing evidence that can improve the human condition. I believe this is an excellent model for interdisciplinary research,” Hall added.