Mar 04 2022

Published by

NYU Shanghai

People make choices every day. From simple ones like what to eat for lunch, to complex ones such as choosing between a well-paid job that requires frequent overtime versus a lower-paying one that allows work-life balance. When there are no objectively correct answers and the decisions are driven by subjective preferences, making choices can be tough. Although friends and family might advise you to “follow your heart” in such situations, NYU Shanghai Assistant Professor of Neural and Cognitive Sciences Cai Xinying has found that what you’re really listening to is the orbitofrontal cortex.

Scientists refer to complex choices involving the computation and comparison of values of each option during the decision-making process as “economic choices.” Decades of research by neuroscientists around the world to determine which parts of the brain instruct economic choices have left us with two candidates for the “key leader” in economic decision making - the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACCd). Naturally, the following questions are: Which one of them plays the fundamental role? Or are they both crucial? How do they function exactly during the process?

Cai, a core faculty member at the NYU-ECNU Institute of Brain and Cognitive Science at NYU Shanghai, recently found an answer to the OFC versus ACCd controversy and proposed a cognitive map to summarize the decision-making mechanism in the relevant brain region. The two studies were published in the leading journals eLife and Neuroscience.

OFC Versus ACCd

In 2019, the journal of Nature Communications published a study led by Cai which presented clear evidence confirming that information encoded by the OFC is sufficient to inform economic decisions. But Cai and co-investigator Camillo Padoa-Schioppa of Washington University, still needed to figure out the remaining part of the story: If the OFC is sufficient to inform decisions, is the ACCd required to make economic choice under other contexts, especially when effort-cost is involved?

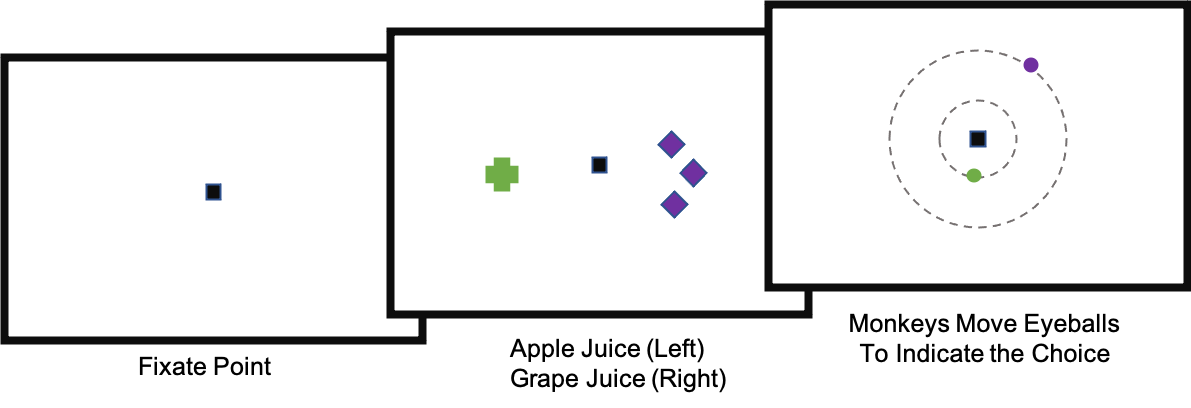

The scientists trained monkeys to perform economic decision making tasks - choosing between different goods (different types of juice), offered in variable amounts and with different effort required to obtain them. The steps in the experiment were spaced out over time so that the monkeys’ computation of how much effort was needed to obtain the juice took place separately from the process of actual action planning. This meant that monkeys only needed to consider how much effort was required to get the juice instead of really deciding how to get it.

By recording and examining the neuronal activities in the monkeys’ ACCd during the decision making process, Cai and Padoa-Schioppa discovered that the ACCd only encodes post-decision information. “Information encoded by ACCd is related to the choice outcomes. In other words, it doesn’t instruct the choice itself but might play a role in guiding the ensuing action plan. For example, ACCd doesn’t tell you which supermarket to go to, but might help you plan how to get to the desired one,” said Cai. “With the evidence presented in this study, we excluded ACCd and narrowed down the potential ‘key player’ in economic decision making to OFC, so future research efforts can be more focused.”

Cognitive Map for Economic Choice

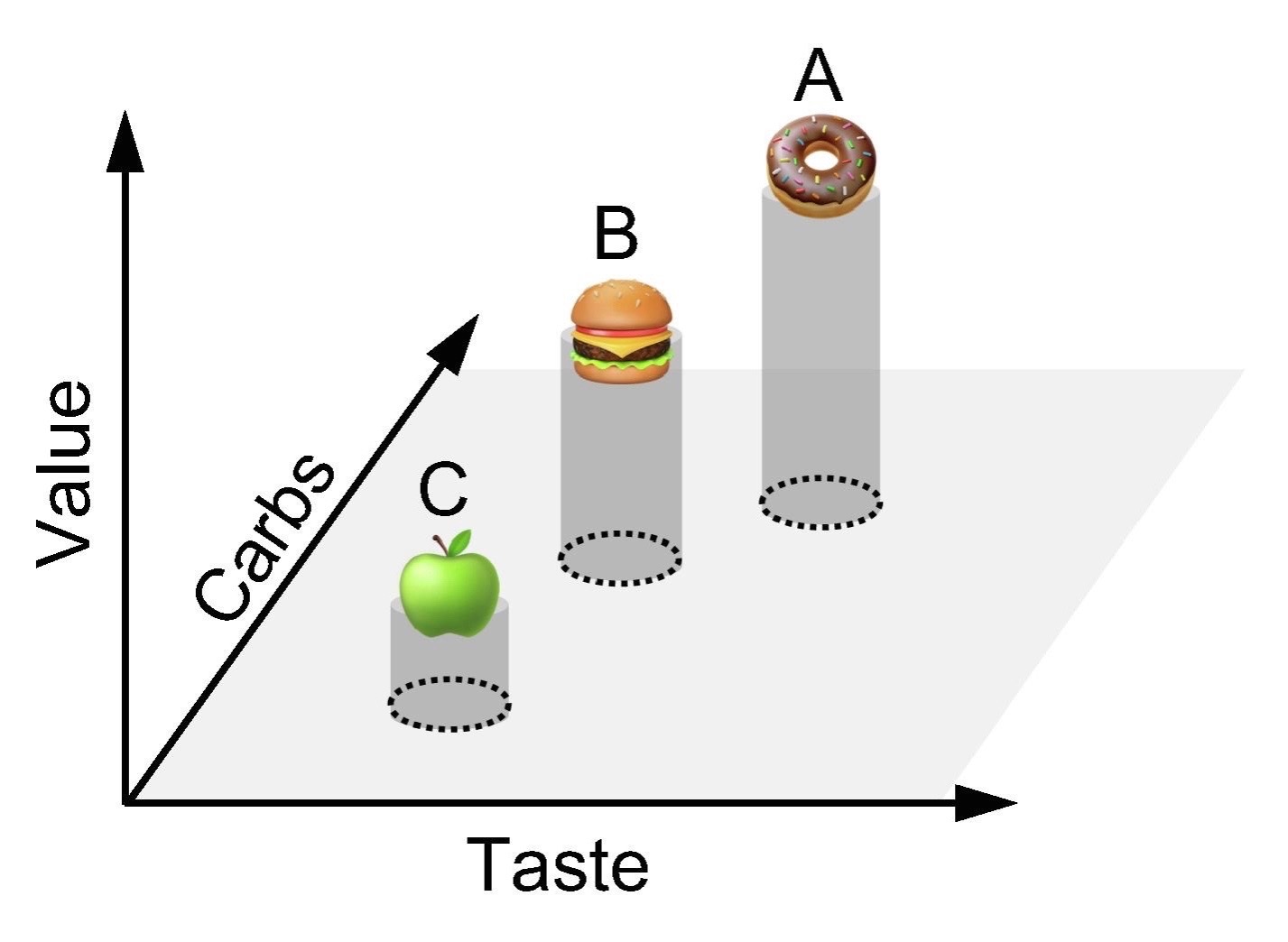

After establishing the OFC’s leading role in economic decisions, Cai interpolated the results of previous studies in this field to propose a cognitive map describing the process of economic choice decision making in the OFC. His review paper offers a detailed analysis of how information is organized in the OFC to guide the choice.  “The ‘map’ in this context is an abstract concept,” said Cai. “Imagine that each time we make a choice, we process the information through an algorithm. Different algorithms are applied to make different decisions depending on specific contexts. Sometimes we may encounter similar choice situations where we do not have to establish new algorithms but can use the ‘old’ ones. Think of the map as a computer program that contains multiple sets of algorithms to accomplish two tasks: One, to analyze the context and select the appropriate algorithm for the situation; and two, to run the algorithm and generate the choice outcome.”

“The ‘map’ in this context is an abstract concept,” said Cai. “Imagine that each time we make a choice, we process the information through an algorithm. Different algorithms are applied to make different decisions depending on specific contexts. Sometimes we may encounter similar choice situations where we do not have to establish new algorithms but can use the ‘old’ ones. Think of the map as a computer program that contains multiple sets of algorithms to accomplish two tasks: One, to analyze the context and select the appropriate algorithm for the situation; and two, to run the algorithm and generate the choice outcome.”

At the current stage, evidence only supports the existence of this cognitive map in economic choice processes. In the future, Cai will conduct further studies to see whether the map also functions in other types of choices, for example rule-based choices, with funding support from the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology. Findings in this area may help us understand how decisions are made in general, and provide new treatments for mental disorders relating to decision-making, like addiction, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and anxiety, etc.