Apr 17 2015

Published by

NYU Shanghai

NYU Shanghai Assistant Professor of Neural Science Jeffrey Erlich recently published in eLife, which features research in the life sciences and biomedicine from the most fundamental and theoretical work, through translational, applied, and clinical research.

His research, titled Distinct Effects of Prefrontal and Parietal Cortex Inactivations on an Accumulation of Evidence Task in the Rat, clarifies the precise roles of two brain regions: the frontal orienting fields in the prefrontal cortex and the posterior parietal cortex, as related to the gradual accumulation of evidence in decision-making.

“Imagine that you have to buy a computer before the start of the school year. You have a few options, such as a laptop or a desktop, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. A laptop is relatively light and portable, whereas a desktop has more memory and is cheaper. You will gradually accumulate evidence for and against each option, but before school starts, you have to make a decision.”

Erlich’s research mentions that gradual accumulation of evidence for or against different choices is considered a core decision-making process implicated in value-based, social, economic, gambling, memory-based, numerical comparison, visual search and perceptual decisions.

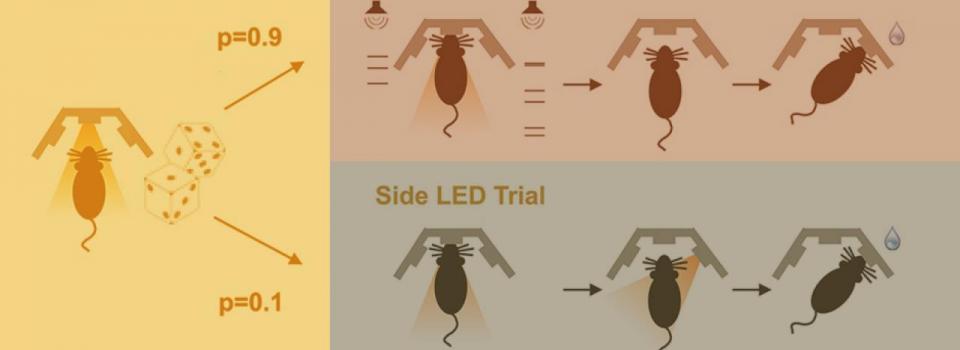

The experimenters trained rats to perform an auditory evidence accumulation task—listening to a series of clicks from two speakers, one to their left, and one to their right—and determining which speaker, left or right, had the most occurrences of clicks.

Using a drug called muscimol to render the rats’ posterior parietal cortex inactive did not affect their ability in decision-making with accumulated evidence. However, when the same drug was used to silence the frontal orienting fields, decisions were driven only by evidence accumulated just over the most recent few hundred milliseconds.

The research showed how the prefrontal cortex (but not parietal cortex) of the rat is obligatory for decisions guided by auditory evidence accumulating longer than 240ms, but the accumulation process itself seems to happen elsewhere in the brain.

As for the computer example, “Without the help of the frontal orienting fields, you would choose the laptop if the most recent piece of evidence was for the laptop, even if older evidence argued strongly for the desktop.”

The study’s other authors were Bingni Brunton (University of Washington), Chunyu Duan (Princeton University), Timothy Hanks (Princeton University), and Carlos Brody (Princeton University).

Written by Charlotte San Juan